You have read that it takes 10,000 hours of practice to master a skill. Yet the Archive exists in a realms outside of time — neither day nor night, hunger nor exhaustion, exist to indicate it’s passage. With no other markers of time, you begin measuring it in skills learned: languages, dances, myriad forms of art and instruments. With limitless time and limitless knowledge available, you perfect more and more skills at a cost only of time — time that means nothing in this place.

Outside of combat, D&D’s main action resolution mechanic is the Ability Check: a d20 roll plus an Ability Modifier, and possibly plus a Proficiency Bonus. Frequently, this is expressed as a skill check — common activities are covered by a list of skill proficiencies a PC may or may not have, and are associated with a default ability score.

Time to overthink how it works.

Action Resolution

Action Resolution is how the mechanics of a TTRPG interact with the fiction. At some point, normally chosen by the DM, the game switches from story telling mode to dice rolling mode. Once the dice rolling is done, story telling mode resumes.

To do this well, an action resolution mechanism must carry consequences for failure, and must be an engaging activity. Consider 5e’s combat: action resolution when two groups decide to fight. The consequences are clear — DEATH. It is also engaging, as every player gets to do something, and lots of class abilities mean every PC has a chance to shine.

But what about the simpler mechanism?

Skill Check

A skill check is not necessarily consequential nor engaging. Rolling one dice at the DM’s request, and adding the requested modifiers, is not engaging, as the player has no agency. Failing an ability check carries no consequences (in a strictly mechanical sense).

Consequences

First, consider consequences, as this is easier to fix. The DM must do something, which can be narrative or mechanical (or both).

Narrative costs are situational. The PCs can either fail, or fail forwards. Failure represents a lost opportunity — the PCs can no longer take a certain approach, and must take a harder or more dangerous path. Failing forwards means the PCs have succeeded, but at some cost that will introduce a complication. As an example, consider PCs breaking into a manor who fail a stealth check. A total failure would be setting off the alarm, preventing the PCs from sneaking it, and forcing them to fight if they want to gain access. Failing forwards might mean the PCs get in, but have to break a window. They have progressed in the story, but the evidence they have left behind means the alarm will be raised soon, and escaping this way will be difficult if they cannot fix things.

Mechanical costs are easier to define, but less flexible. They may inflict conditions: a stressful close call might leave the PC Frightened, while a hard climb Exhausts them. The DM could also inflict damage, or consume some other resource or gear if available.

The third (secret) consequence is the Missed Boon. Sometimes it might be possible for the PCs to gain an unexpected edge, like an insight into their enemy’s strategy. In these cases, failing a skill check is not a set back, but a missed opportunity. Take care with this. Unlike the other consequences, this does nothing to prevent repeatedly re-attempting the check until the players succeed. This removes the risk of failure, negating the point of the skill check, so should not be allowed. If the option is there, there is no need for a check — the PCs just succeed automatically, and the game remains in story mode throughout.

Engagement

Engagement is tricky. Sometimes, we want to make a challenge intricate and involved. Other times, we want to have a quick skill check and get on with the rest of the game. There is no one-size-fits-all solution here. Instead, we must exercise DM’s judgement.

For simple challenges with one obvious approach, requiring a specific check makes sense. However, much of the fun in TTRPGs comes from applying creative solutions to problems. Rather than providing lots of simple challenges, we can create more complex ones with multiple approaches. Consider the example above of breaking into the manor. Clearly, the PCs can use stealth, but they could also bluff their way past the guard, or intimidate them into staying quiet, or use their athletic prowess to climb an unwatched approach, or use a spell.

Informing the players they they have reached an obstacle that will require a skill check, then letting them decide how to approach it is very powerful. As DM, you know they will need to make the check, so will be appropriately challenged. You also no longer need to think up every last challenge. The players will have the freedom to be creative, and can use their skills as a source of inspiration.

Skill Challenge

A final, useful variation on the skill check is the skill challenge. Matt Colville explains the idea here. Rather than repeating what is explained better elsewhere, I will tie it back to Engagement and Consequences.

Therre is a lot more space for varying consequences with skill challenges. The whole challenge could carry consequences, using the normal model of “get X successes before X failures.” Alternatively, each roll could have consequences. In this case, the skill challenge determines what the cost is. Rather than requiring a certain number of successes, this should require a certain number of checks regardless of outcome.

Skill challenges encourage engagement both by being flexible, and by encouraging each player to contribute in different ways.

Skill Difficulty

The maths behind skill checks is the same as for attack rolls, so the difficulty of skill checks can be set in the same way as AC. Interestingly, this is not what the DMG does. The table of monster statistics on page 274 maps Challenge Rating to AC — it tells us the appropriate AC to challenge a party of a given level. The skill DC discussion on page 238 give more abstract descriptions of difficulty (Easy/Moderate/Hard). Both tables do something similar: they tell us the DC/AC values that are easy or hard. The difference with the monster table is that it tells us how hard a challenge PCs of a given level should attempt.

As with many of D&D’s quirks, this is due to verisimilitude. Anyone could attempt any skill challenge, so that should not be tied to level, should it? Except, that is also true for monsters. A level 1 PC can attack a Balor, and a level 20 PC can attack a kobold.

If we are attempting to create a balanced adventure — one that will be challenging, but still “winnable” — we should set skill DCs in the same way as AC. This does not mean we change how difficult tasks are, but that we select which challenges we resolve in fiction, and which in mechanics. A certain crag may be insurmountable for low level characters, climbable for mid level PCs with a check, and not worth mentioning at high levels.

Skills in Play

After looking at how mechanics work, we can consider how mechanics are used. In particular, we can consider the list of possible skill proficiencies in 5e. Ideally, every skill should be valuable, and no skill should be essential. The game should not let players make exceedingly poor choices, nor offer the illusion of choice when only one option is good. To learn if this is the case, we need data.

Skills All Round

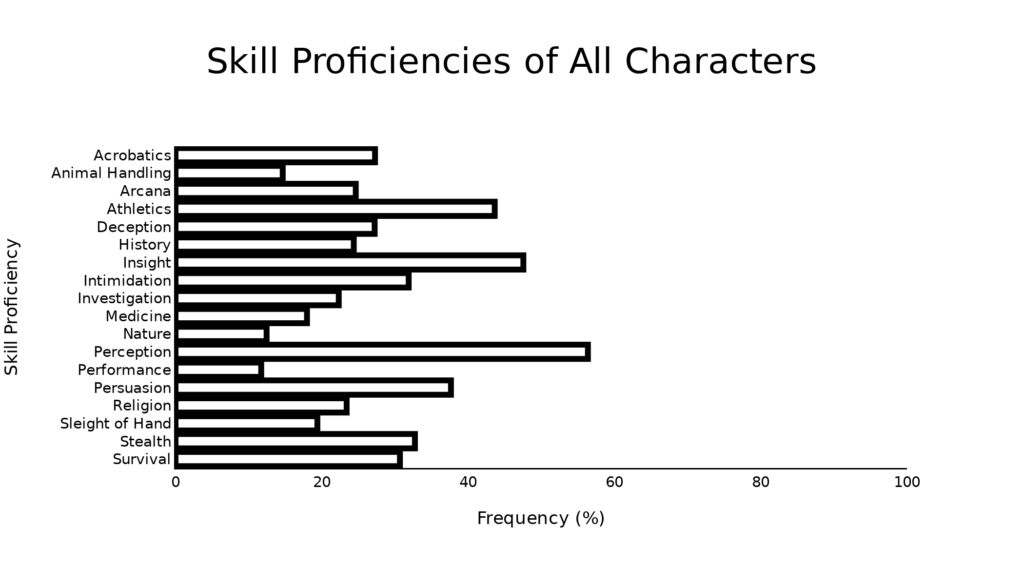

First, we can look global data. The above figure shows the percentage of all characters who have a particular skill proficiency, whether from race, class, or background. Unsurprisingly, Perception and Insight are very common. Perception in particular is extremely versatile — there is no situation in which being able to spot things is not helpful. Performance and Nature are at the other extreme, being too niche to use while adventuring.

There are lots of variables at play here. Skill choice is limited by class, so it is possible that the infrequent selection of Performance is because no one can choose it, rather than because no one wants to choose it. Similarly, the high frequency of Perception may be because all elves have it automatically, rather than because players choose it. To be more insightful, we can look at the data by class.

Skills By Class

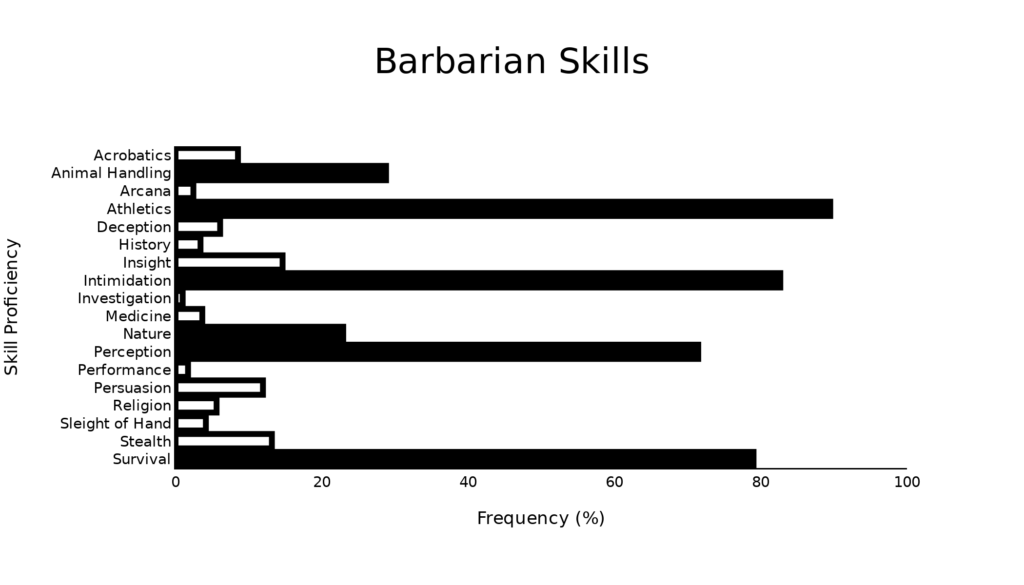

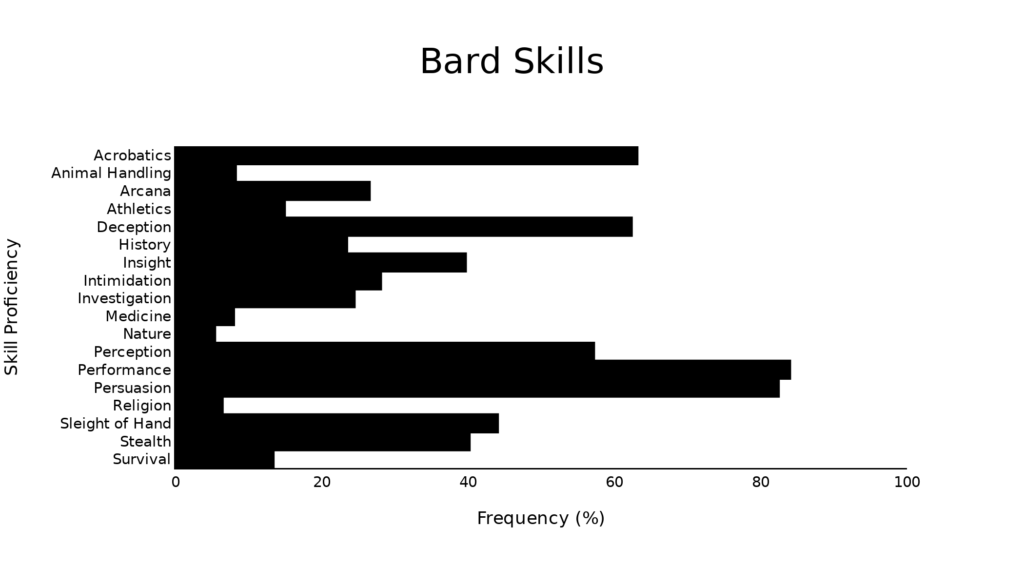

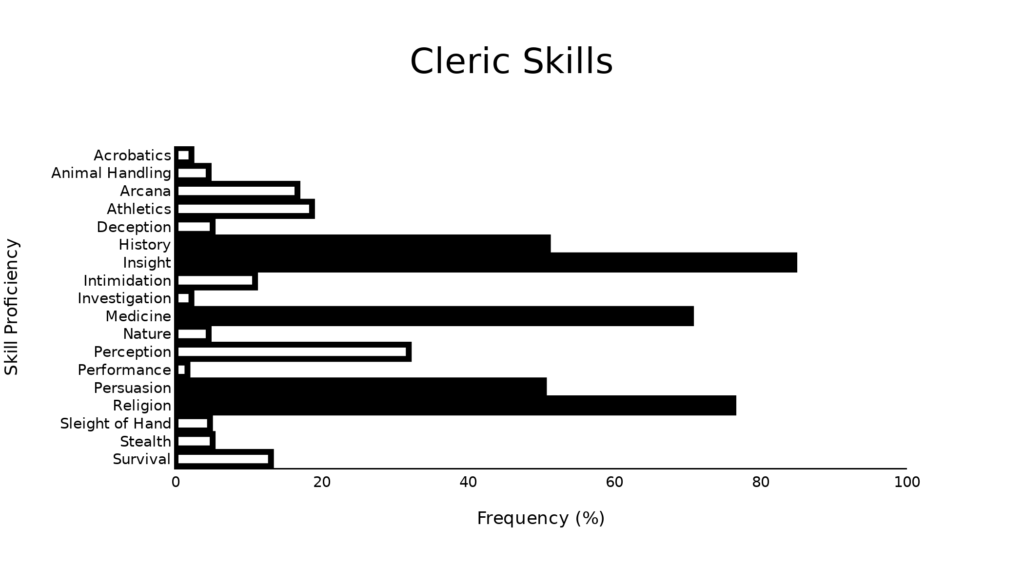

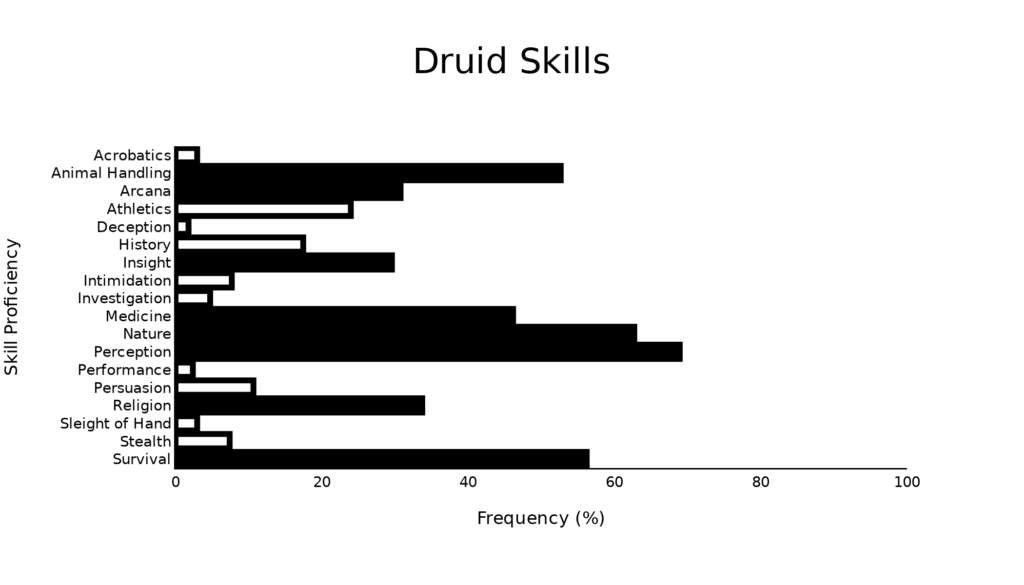

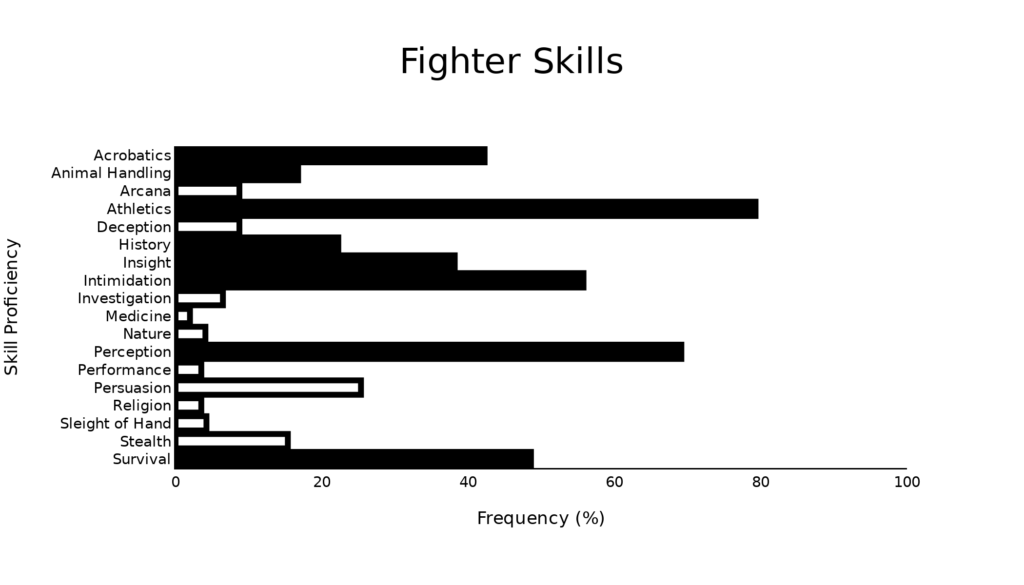

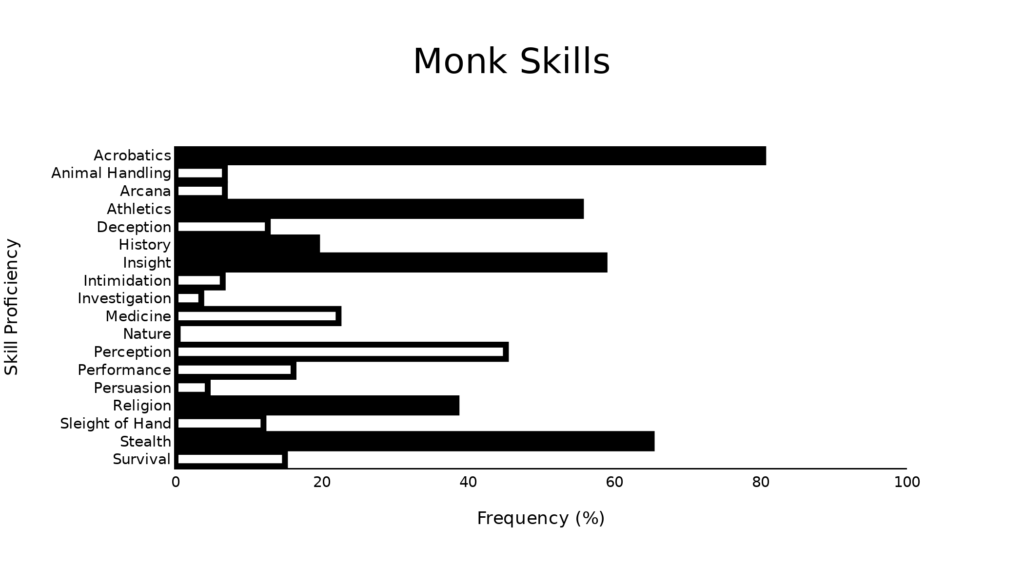

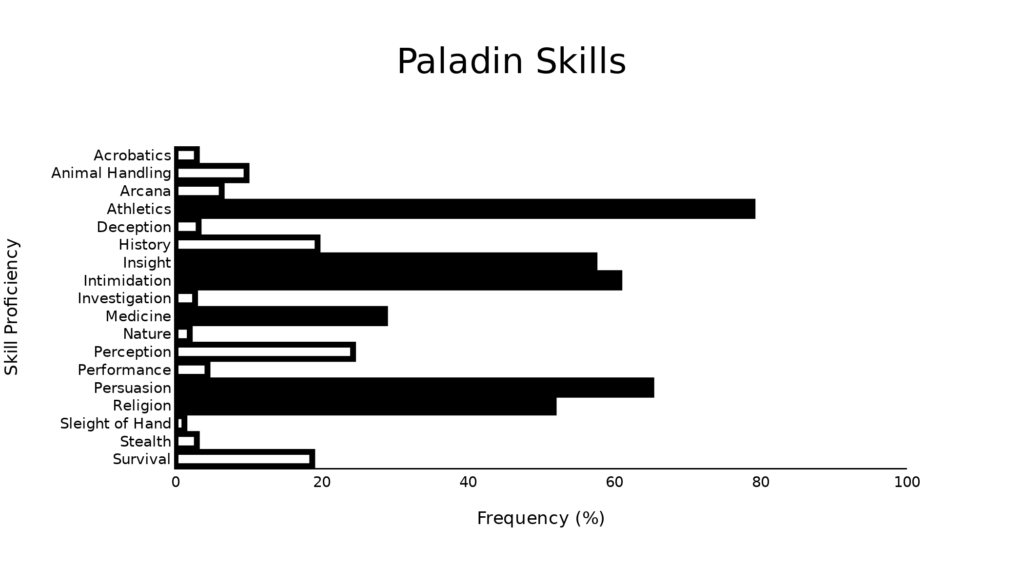

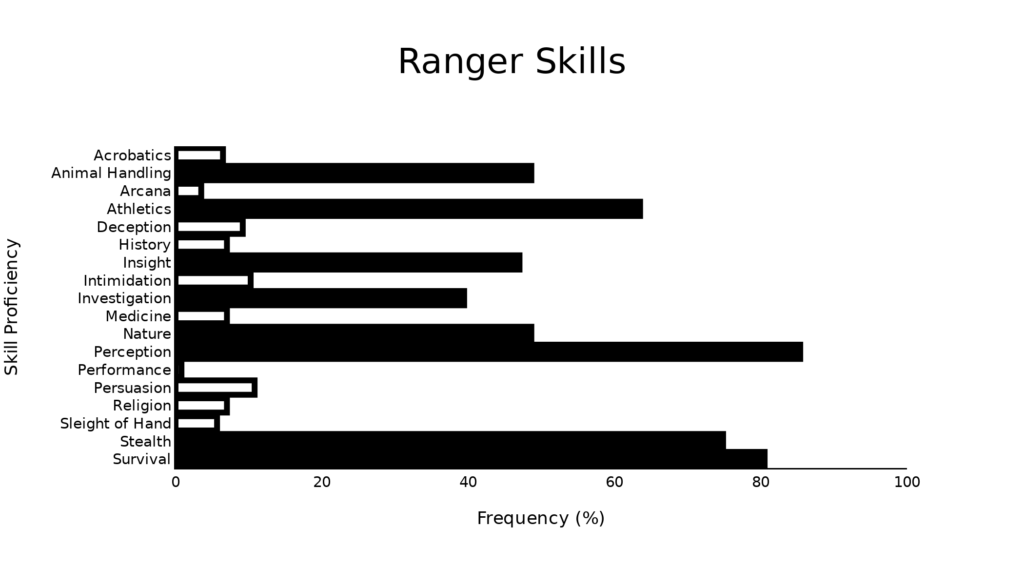

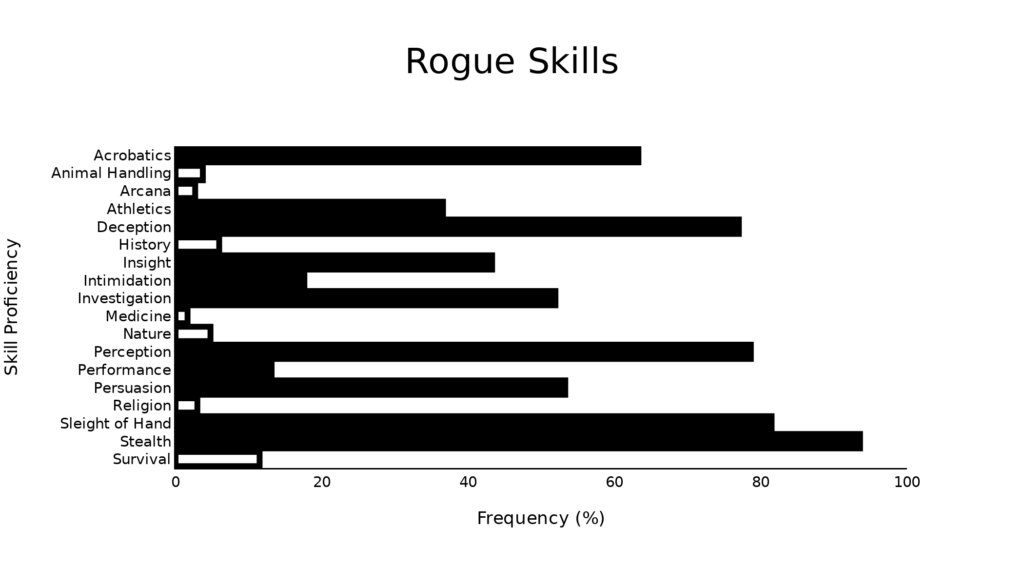

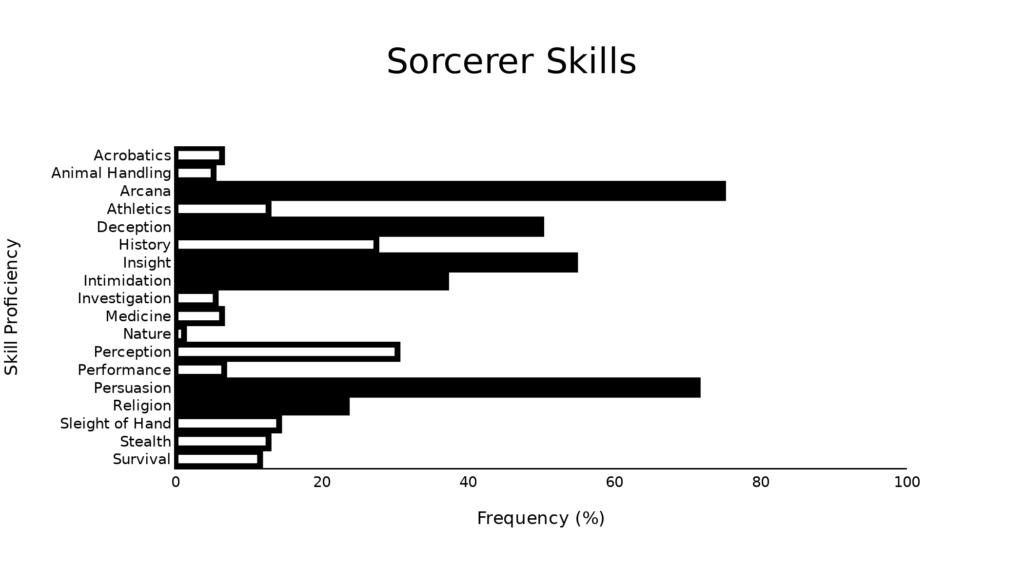

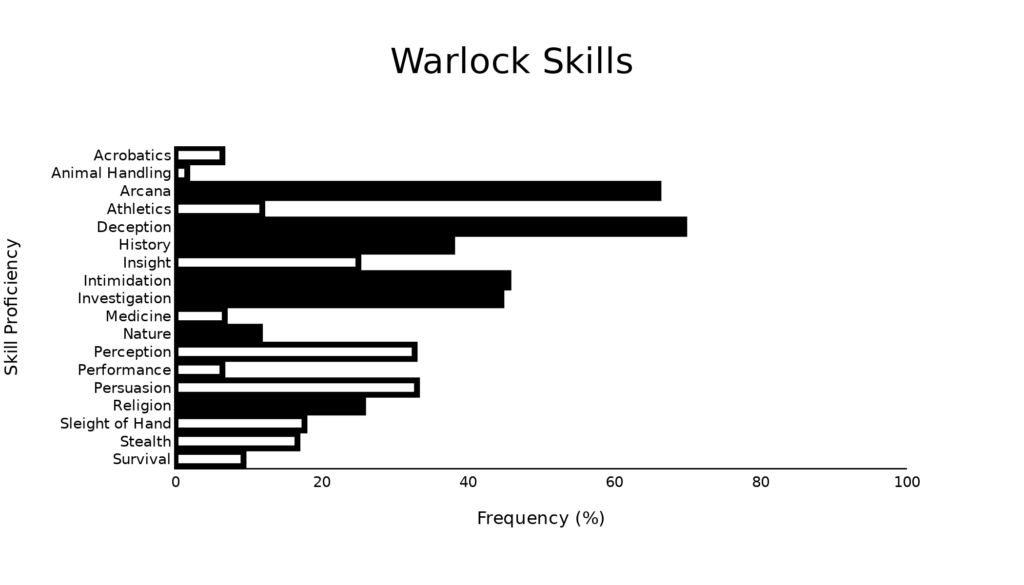

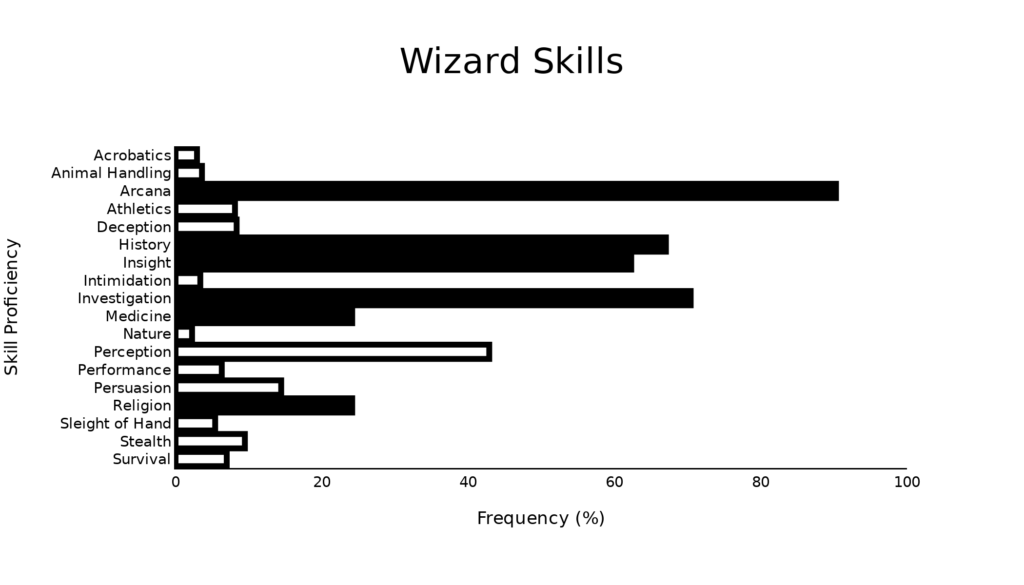

The figures at the bottom of the page again show the frequency of each proficiency. In each figure, the data has been filtered to a single class, and the skill proficiencies available to the class have been highlighted in black.

Perception

In every class that offers Perception as an option, Perception is frequently chosen. In addition, every class that does not offer Perception still has it as the most frequently chosen proficiency from other sources (except the Warlock, where it is tied with Persuasion, likely due to Beguiling Influence). We can be confident that Perception is a highly desirable skill, given that it is universally popular.

Differing Choices

The Barbarian figure is interesting. Of the six available proficiencies, four are massively more common that the other two. Once we have ruled out other influences, and offer them only a straight choice, players have a preference for the other skills over Animal Handling and Nature. The same can be seen for Animal Handling in the Fighter, History in the Monk, Medicine in the Paladin, Intimidation and Performance for Rogues, Religion for Sourcerers, Nature for Warlocks, and Religion and Medicine for Wizards.

This list (Animal Handling, Nature, Religion, Medicine, Intimidation, and Performance) highlights the bad skills, from a player perspective. They are considered ineffective, uninspiring, or inferior to other options, so perhaps we should consider ways to improve them.

Animal Handling and Medicine are both highly specific Wisdom skills. We could combine them into a single “care for life skill” — perhaps ministration. This would have a slightly expanded use, so would be more attractive as an option.

Nature and Religion normally relate to knowing things. As information is frequently revealed as part of a campaign or adventure anyway, this is often not essential. We could combine them with Acrana to create a scholarship skill that covered any kind of academic study or note taking.

The Rogue’s aversion to Intimidation is interesting. They do not shy away from Deception and Persuasion, the other social skills. The data instead suggests a widely held belief that Rogues should not Intimidate, but deceive and convince instead. Bards and Sorcerers show similar data. Paladins are the exception, but even then it is a matter of degree — there is still only a slight preference for Persuasion over Intimidation. I suspect that Persuasion and Deception are preferred because you can “get away with it” — unlike someone who is intimidated, the PCs may escape suspicion with these skills. However, Intimidation is still taken by enough classes that we can consider it a functional choice for at least some characters. We do not need to change anything here.

Finally, Performance. This skill is taken by almost no one, except Bards, and is taken by almost all Bards. It is a choice, but it swings between being an undesirable, irrelevant choice, and an essential character feature. A potential solution would be to establish proficiency in a class. Clerics would be proficient in Cleric activities, like performing religious ceremonies; Rogue proficiency might apply for underhand dealings and thievery; Bard proficiency would apply to all their performances. This creates a new integration of class archetypes and skill checks.

Skill Mastered

That covers how skills work! Hopefully you have some ideas about how you can use them in your games, or hack them into something better. The data and figures (also on GitHub) should help you understand the trends in player preferences, and why they might prefer certain options to others.