The Archivist has tasked you with clearing up an outbreak of mildew in one of the older libraries. While drying out the damaged book and carefully removing the stains, you find one tome affected more than most. Strangely, the fungal growths that damaged the other writings appear almost decorative on this one. The words and diagrams are clearly visible, and the coloured patched of mold on the cover seem only to make it more eye-catching. Visible between the patches is the title: Utumral.

In the Beginning

There is no obvious place to start when creating a universe, but there is an obvious place to start a game of D&D: with an adventure. That is what we are here to do. But creating an adventure — a good adventure — takes time and careful thinking.

First, time: writing this adventure is going to take several posts. Today, I will detail a high-level plan for a D&D 5e adventure. This will be the scaffolding for building everything else. With that in place, future posts will add details like rooms, monsters, and maps. If we ever reach the end, I will put the finished adventure together in one place for you to try.

Second, careful thinking. There are lots of moving parts in an adventure (even before the players arrive), and there are lots of missteps that can have significant unintended consequences for how the game turns out. Whenever I take efforts to avoid these problems, I will highlight them. I wish I could make a clear distinction between important decisions driven by mechanics and flexible decisions driven by creativity, but that is not how the game works. There is too much overlap between the two. Instead, I will highlight the principles I keep in mind while working on both mechanical and creative aspects.

One more thing. Adventures or dungeons or modules (I use these terms interchangeably) are necessarily tied to the rest of the game. Sometimes my way of running games will inform my decisions. Rather than explain every last tangent, I will skim over those details, and cover them in later posts elsewhere — otherwise we would be here to eternity.

With that out of the way, it is time to start!

Principles of Adventure Writing

Depth

A well-written adventure is more than a chain of randomly selected encounters. The encounters must be linked by a story. This story is what keeps players connected with the game as they move from one event to the next. It is also makes recurring games easier to schedule, as the players become invested in the big picture.

A well-written adventure plot can also empower players to try new ideas. If the factions involved in the adventure have understandable motivations and behave in the expected fashion, the players are better placed to find creative solutions, and to anticipate how the groups will respond to them. This helps them make informed strategic decisions, and take satisfaction in plans that come to fruition.

To achieve this, the story must offer sufficient depth. At the same time, care must be taken not to make the story too complex. If players need documents of lore to have a chance of understanding the adventure, it is too hard. They will forget or confuse important details, which forces the DM to either interfere, disrupting their independent planning, or force them to face the consequences of such mistakes, which breeds frustration. Adding extra flavor is great, but making perfect knowledge of these extra details critical is likely to backfire.

Diversity

An adventure is a collection of problems that the players must solve using a variety of abilities. If every challenge they face has the same solution, the game will stop being engaging. Contrast tic-tac-toe with chess. Once you have played enough tic-tac-toe to understand the strategy necessary to force a draw, the game becomes repetitive and offers nothing new. On the other hand, few people have enough experience for every possible game of chess to be familiar. To keep players interested, an adventure must offer a wide selection of problems with different solutions.

Fortunately, the mechanics of 5e provide a good diversity of mechanics. We can use non-combat skill challenges, or combat encounters. In combat, we can use different monsters and map layouts. For variety, we can throw in the occasional roleplay-only challenge.

There is, however, a caveat: in the same way that limiting complexity informs strategic decisions, limiting variation informs tactical decisions. If a particular dungeon is full of tripwires, the players should learn to look for them. If every trap were unique, they would be unable to search in an informed way. Similarly, using a limited deck of monsters lets the players learn the strengths and weaknesses of each, while still providing enough variation to keep combat interesting.

Pacing

Pacing in an adventure is complex — not because it is hard, but because it applies to multiple layers. Both the story and the game needs appropriate pacing.

The pacing of the story is easier to grasp, as it applies to any fiction. A good story builds tension, then resolve it at the climax. On the microscopic scale, this unfolds within each scene. In an episodic show, this also plays out between episodes, with each resolving its own story, but contributing to the growing tension of the season’s plot. Trying to maintain an intense, dramatic moment throughout an entire story inevitably fails because players grow used to it. Continually building and releasing tension keeps players focused on the moment and engaged with the game.

From a game perspective, pacing is a little different. D&D 5e has a less-than-obvious quirk when determining difficulty. Given two identical encounters, the second one is harder. To explain, we need to look at the maths of resource management. The game has an attrition model: over the course of an encounter, hitpoint, spells slots, and other features are consumed. Once expended, the PCs cannot use them until some recharge condition is met, such as resting or buying new potions. When facing a second encounter, the PCs will have fewer resources than the first time around.

Attrition is a very powerful tool for pacing. It creates a growing sense of tension, as each encounter weakens the party. By the time they reach the final boss, they will be getting desperate. However, players can break it. If they stop to rest, the clock resets. The tension is gone, but the climax has not been reached. Resting in 5e is very easy, and this is generally good: it empowers players by encouraging them to take stock of their position, and rest if necessary. However, it makes pacing harder. As we write an adventure, we will need to find a solution. There are several, including doing nothing. My goal here is not to convince you to use the perfect solution, but to be intentional in whatever solution you choose.

Game pacing will also influence dungeon layout. Every fork in a tunnel is an opportunity for the players to change the order in which they face challenges. Perhaps they will find a quicker route to the boss, avoiding attrition; perhaps they will search every room, expending significant resources. Again, there is no right or wrong solution here. What matters is that we understand the consequences of how we arrange the adventure.

It is worth keeping pacing in mind within encounters, although they are harder to get wrong. In a combat encounter, tension builds until the PCs overcome the enemy, at which point the encounter ends. With non-combat encounters, it can be subtler, but the encounter is still about tension building until it is resolved.

Fair Play

A frustrating reality of tabletop RPGs is that we must compromise between consistent, rational enemies and achievable game objectives. The problem is that most enemies smart enough to be considered a threat are capable of stopping whatever the PCs try. Even low-level bandits can create defenses that are nearly insurmountable for a party of four. Believable enemies can quickly make the game unwinnable. To avoid this, we must maintain a sense of fair play when writing adventures. While we want them to be believable, we also want them to be possible, and sometimes this means compromise.

Anyone who is familiar with a video game’s stealth mechanics will recognise this. We know that real enemies would raise the alarm if patrols started silently disappearing, but as that would make the game impossible we suspend our disbelief. The same applies to adventure level: there is no in-world reason that the challenges facing a 20th level party must be harder than those facing a 1st level group, except that no player would want to fight an ancient red dragon at 1st level, or bother facing a single kobold at 20th.

The takeaway here is that it is not only acceptable to compromise believably for the sake of fun — it is necessary.

The Adventure Pitch

Now that we have some guiding principles, it is time to create an adventure. The first thing we need is a pitch. This is a short creative nugget from which to grow the adventure. It should capture the feel of the adventure we want, and give the PCs a motivation to get involved. We also need to choose a game system, and a level range if appropriate. Finally, it is good to come up with a name so that we can attach any ideas we have in future to a handy label, not just “the third of the eight adventures currently in my head.”

So, here we go:

This dungeon of Utumral is a plant-themed ruin from an ancient civilisation. Archaeologists wish to explore it, but are cautious of hazardous mold and defenses left by the previous inhabitants, so have hired adventurers to secure it for them. This is a D&D 5e adventure aimed at a party of 4 characters between levels 3 and 5.

That is all we need to get started. The PCs have been hired by archaeologists who just want it to be safe to investigate. The monsters and challenges will either be relics of the ancient civilisation, poisonous mold, or plant monsters. And we have a rough sense of difficulty, although we can fiddle with that later.

The pitch is our starting place. From there, we can add some more dungeon-wide details.

The Biggest Picture

To ground Utumral in the world, I need to establish a few background details. This gives me space to add hooks for future adventures, and creates a safety net in which I can improvise. It can also provide inspiration for little details that are at odds with the rest of the dungeon.

As Utumral is plant-themed and tied to an ancient civilisation, those are good places to start. What if it were the earth-part of an elements-themed collection of nations? I could add hooks to future adventures in these other nations, or draw on them to add unexpected components, like an automaton given as a gift by the fire nation.

Players will almost certainly be familiar with a four-elements theme, so should catch on. To give some in-world context, I can add some mythology: although allied, each nation worshiped a different elemental deity. This pantheon is still worshiped today, although the names and traditions have mutated.

As well as giving PCs an excuse to know what players know, this grounds Utumral more firmly in the world. As this history is uncovered, maybe a group of priests will come to investigate, either to uncover their lost history, or hide it and preserve the status quo.

Finally, I need to establish a timeline. To fit into my normal setting, I have decided Utumral was abandoned about 1500 years ago. As I develop the dungeon, I will add more details about how and why this happened, but for now I am intentionally leaving it vague so as not to constrain my options.

The Big Picture

Zooming in from the wider world, let’s focus on the site of the adventure.

Utumral Today

Firstly, the present day. The site has been uncovered by random chance, and brought to the attention of scholars. The scholars want to explore, but it is dangerous, so they send stronger, less intelligent adventurers in to make it safe. In payment, the adventurers can keep any items they find, although the scholars would like to examine them first and offer to buy them.

This serves several purposes. Firstly, it is a motivation for the players: go underground and kill things, then get paid. It also adds an opportunity for getting lore, as the PCs can consult experts. Finally, the scholars provide a way for me to control pacing.

As I said, there are many ways to manage pacing. My solution here is to break the dungeon into chunks, each designed to be explored in a day of adventuring. I can enforce this through the scholars, who will only give bread and board if the PCs pull their weight, forcing them to complete each adventure section before taking a long rest. The same method will also break up sessions: each “day” should fill a game session, giving the players a chance to use a mix of abilities, win some treasure, have a boss fight, and make progress by unlocking a new area. Another advantage of this method is that it keeps players moving — knowing there is a certain amount of content to get through in the session encourages them to be more decisive, and to remain focused on the game.

Utumral of Old

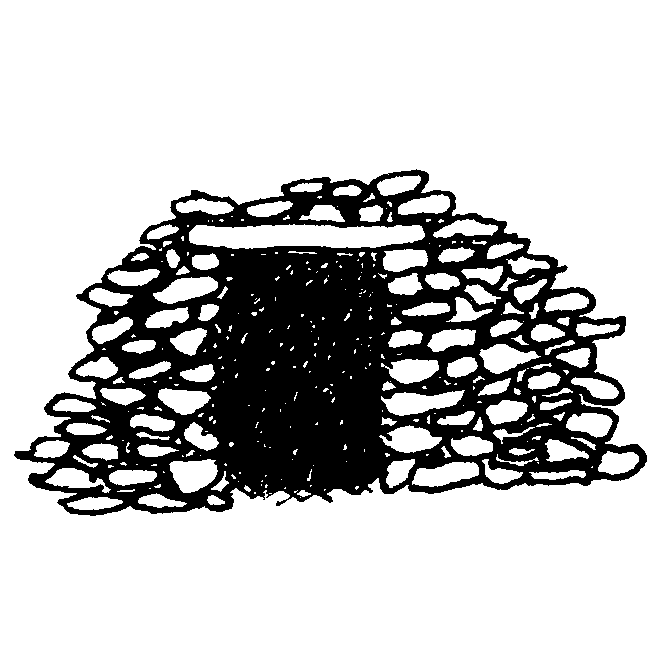

A good mental picture of the dungeon will be helpful both for improvising descriptions, and for finding inspiration about what it might contain. Rather than trying to create this from scratch, I am going to base the aesthetics of Utumral on the neolithic settlement of Skara Brae. I’m familiar with it both from pictures and from visiting, so can make up descriptions on the fly while maintaining a consistent picture of the location.

At this point we can also draft an initial monster deck. Although this will change as the dungeon evolves, it can still serve as a starting point. As a plant dungeon, the monster deck will include poisonous fungi, some kind of killer plant, and an ooze. These hazards are what I call Denizens — monsters that live in the dungeon, and are by nature hostile. Players can kill them or avoid them, but their motivation of primitive violence makes them impossible to reason with.

The Faction that controls the dungeon will also be in the deck. This is normally a more complex group with varied tactics and unit types, but a common motivation. The faction in Utumral will be some kind of ancient guardian, created by magic and bound to protect the sacred places. In keeping with the theme, they will be plant-based rather than undead. Their motivation is worth examining: as magically compelled guardians, they cannot be reasoned with, but it is possible they could be tricked. Perhaps if a PC finds and carries the staff of the archdruid the guardians will allow them to pass.

The Little Picture

Next time, we’ll start on the little picture: fleshing out rooms and monsters to turn this into a real adventure.